Author, D.C. Corse Stops by to talk

Getting it Write: Researching the FBI in a post-9/11 America

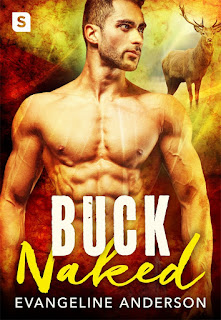

D.C. Corso, Skin and Bones

Most mystery writers will agree that if you ask the FBI for an interview on procedures to ensure accuracy in your book, you’ll get a polite response that everything you could possibly want to know is on their official website (read: everything they feel comfortable sharing is on their website). Despite any initial disappointment that a Real Live FBI Agent will not be advising you, the FBI website really does hold a wealth of information. Everything from department names and functions to statistics can be found at www.fbi.gov, including links to other agencies and all the various Field Offices.

Not a fan of the internet? There are plenty of books out there by retired agents; the most readable ones are aimed at the mainstream true crime-reading public (such as former agent John Douglas’ intriguing Mind Hunter). There are also plenty of procedural guides out there that give a more historical spin and really read more like reference books. If you’re trying to get an idea of what a behavioral profiler is trained to do, the more academic texts written by agents are extremely helpful. For instance, BSU co-founder Robert Ressler’s unfortunately-titled Sexual Homicide: Patterns and Motives – a text which I am too self-conscious to give away or read in public, as if people who see it will think it’s a how-to book.

I have pages upon pages of notes taken largely from the FBI site. But how much do the readers care about technicalities? I assume that they only want to know what they need to know, and write accordingly. I recall my first draft was filled with far too much procedural information which, in turn, required far too much accompanying expositional dialogue. There are simply some things that law enforcement officers do not say to other officers because they already know it. My favorite example of bad expositional dialogue appears repeatedly on television crime dramas; one officer will ask another, “Was there any GSR?” The other will inquire, “You mean gunshot residue?,” for the benefit of those watching at home. It’s necessary for television, but I prefer to avoid clunkers like this; there are always better options in writing.

My first novel, Skin and Bones, is about a small Washington island community affected by a series of child abductions. I chose the days immediately following 9/11 because the shared emotional chaos of those early days was the start of an important shift in the American psyche. There was a short-lived sense of unity among Americans as we all looked nervously to the skies, yet there was also a paranoid sense of self-inflicted isolation among individuals. I had no way of knowing how this affected the FBI, aside from interdepartmental shifts that occurred at the time, which were all well-documented and easy to find via the Internet.

While I did not want 9/11 to be the focus of the story, but rather a backdrop, capturing that feeling did not entail regurgitating facts, but rather keeping them in mind when setting the characters about their business. After all, during this time the general public tended to ignore the more ordinary horrors of local news, fixing our gaze instead on CNN’s coverage of the national tragedies.

This is where the real story lay, I thought – in the forgotten. I wanted to keep the focus on the Missing Persons Squad and how their jobs were perhaps made more difficult by Americans’ intense focus on anti-terrorism. And while research was a must to set the background, only character development and multiple drafts brings reality to fiction.

Comments